Introduction:

We’ve tested hundreds of endurance athletes, and at least 80% have a significant amount of untapped performance potential. Their aerobic base is good, their functional threshold is solid, but their aerobic power is lacking.

Aerobic power is the ability to use oxygen quickly, and is trained through accumulating time above 95% VO2 max. Aerobic capacity, on the other hand, is the ability to use oxygen over a given distance, such as being physically able to complete an Iron distance triathlon, and is trained through your long, slow distance base training.

Most amateur athletes who have been training and competing for a number of years have a decent base fitness (aerobic capacity), but very few have the aerobic power necessary to actually race and compete faster. Aerobic capacity will get you to the finish line, but aerobic power will get you there quickly. For optimal performance, these two should be trained simultaneously for maximum training benefit.

The Physiology:

There’s two primary ways to improve your aerobic ability. One is to complete continuous training at <2.5mmol/L of blood lactate (ie base training); the other is to accumulate ~10 minutes at VO2 max. Both of these sessions stimulate to production of an enzyme called PGC-1a (see below) which in turn increases our aerobic engine.

You may recall from a previous article, that lactic acid inhibits our body’s ability to create aerobic energy; therefore, to improve aerobic capacity and aerobic power (essentially our VO2 max), we want to minimise our lactic acid accumulation during this training.

Aerobic Capacity:

This one is fairly straight forward. Completing continuous training at <2.5mmol/L of blood lactate will improve your body’s ability to consume oxygen. This target heart rate, power, or pace is most accurately measured during a lab test. If you can’t access a lab, 75% of your max heart rate is a good ball park figure to work with (YOUR max heart rate, not a generic equation; what’s the highest you’ve seen your heart rate get to?). Accumulate time at this heart rate to improve.

Aerobic Power:

This is the neglected session, and the one which most readers will benefit greatly from. Accumulating time at 95% VO2 max will take your performance to the next level. It is not exactly specific to racing, but it is phenomenal general preparation before leading into a specific building cycle. The goal here is to accumulate between 12-20 minutes of time at 95% velocity of VO2 max, with identical recovery in between. The intervals for this specific adaptation should always be between 2-4 minutes in length. Shorter than 2, and you won’t accumulate much time at VO2 max. Longer than 4, and you’re accumulating too much lactic acid and probably not truly hitting 95% VO2 max (you should be a 9/10 rating of perceived exertion after 4 minutes)

For example, if your VO2 max power is 360 watts, your target power (360x0.95) is 342 watts. An example session may look like:

6x3 minutes at 342 watts, with 3 minutes recovery at <100 watts. This accumulates 18 minutes at 95% VO2 max, with 18 minutes of very easy recovery. Add in a decent warm up and cool down to round out close to a 1-hour session.

Again, a lab test is the most accurate way to find this target number. An alternative is to complete the following:

Cycling/Rowing:

1. Begin at 60 watts (females) or 90 watts (males).

2. Increase the resistance by 15W every 1 minute. Continue this until you can no longer hold target power.

3. Take the last number in which you finished the full minute stage, and multiply this by 0.95 (eg if you lasted 20 seconds into 375 watts, revert back to 360 watts). This will give you your target number.

Running:

1. On a treadmill, begin at 8km/h (females) or 9km/h (males).

2. Increase the speed by 0.5km/h every 1 minute. Continue this until you can no longer hold target pace.

3. Take the last number in which you finished the full minute stage, and multiply this by 0.95 (eg if you lasted 20 seconds into 17.5km/h, revert back to 17km/h). This will give you your target number (which you can then convert into pace/km).

This is a high quality session which should never exceed 20 minutes of ‘effort’ time (40 minutes in total if you include the rest) and will highly stimulate your mitochondria to increase in number, size, and surface area, so you are able to utilise oxygen much quicker and ultimately perform faster. It is crucial from a physiological point of view to keep the work:rest ratio at 1:1 (eg 2 on, 2 off; 3 on 3 off; 4 on, 4 off); we need to hit 95% VO2 max, and we need to minimise blood lactate accumulation.

Case Study

When you get it right, here’s what can happen: Josh is a triathlete who had a phenomenal aerobic base, and completed a lot of long, slow continuous training. His ability to extract oxygen was elite at low workloads, but he became aerobically inefficient at higher intensities due to rarely completing interval training.

VO2 max before VO2 max training: 69.6

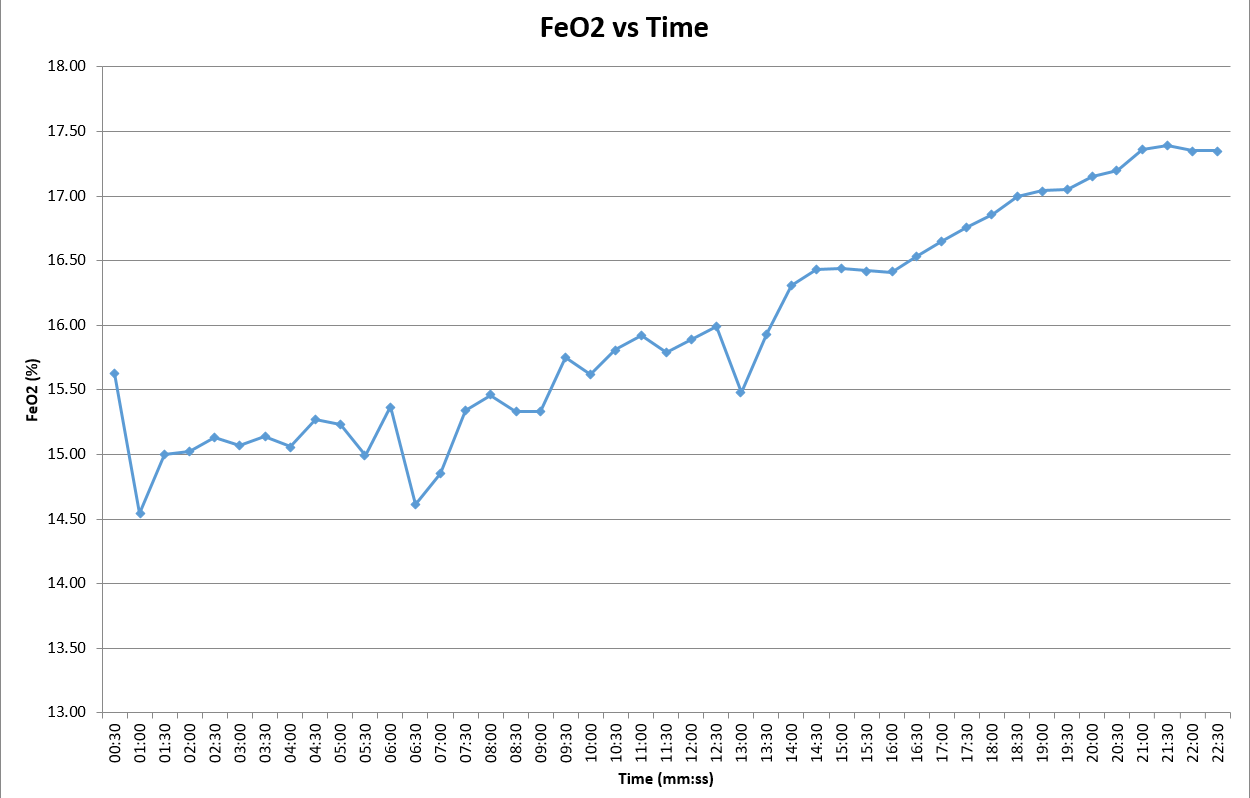

Fraction of expired oxygen before training: steeper gradient indicates poorer aerobic power (and therefore lower VO2 max)

VO2 max after 4 months of including intervals at 95% VO2 max: 80.6

Fraction of expired oxygen after 4 months of including VO2 max intervals: Notice the significantly shallower gradient towards the end of the test, indicating improved aerobic power (and therefore higher VO2 max).

After 4 months of including VO2 max intervals 2x per week (without increasing his weekly volume) his VO2 max improved from 69.6 at 20km/h, to 80.6 at 20km/h + 3% incline. He lasted an extra 2 minutes into the VO2 max test, and hit the podium for the remainder of the 16/17 Gatorade Tri series. This was largely due to an improvement in aerobic power, as indicated in the shallower gradient in his post-training FeO2 graph above.

Summary

- If you feel like you aren’t getting faster, have a try at completing 1-2x VO2 max interval sessions per week at 95% VO2 max velocity for 2-4 minute repeats, with identical recovery, and accumulating 12-20 minutes of ‘effort’ time.

- Be aware of the impact to your body; this isn’t a good session to complete if you’re suffering from an injury.

- Lab testing is a great way to determine where your physiological weaknesses lie, determine accurate training zones, and to get advice on the best training methods for you to improve.

- Click here to sign up to a free membership area which has heaps more information on the science behind endurance training.